My all-time favorite travel game is called Geography: I have fond memories of playing it in the car on the way to visit my grandparents, or with my cousins when we would travel together to Thanksgiving. It’s not an actual geographical game, but a word game made up of place names.

Photo taken in Vatican City, in the Vatican Gallery of Maps, featuring a detail of a map in fresco entitled “Italia Antiqva”. This photo happens to include the towns of Gaeta (the southern-most point of our trip) and Sperlonga (a coastal town I particularly liked), along with some education: it hadn’t occurred to me that the Adriatic Sea (“Mare Hadriatic”) might be named for Emperor Hadrian.

Player one names a place. Player two names a place whose name begins with the last letter of the previous place. And so on.

I say Rome, you say Edinburgh, the next player says Holland. (Or if it turns out you were actually saying Edinboro, then the next player could say Ohio.) No repeats.

If someone says a name that’s come up already, they get corrected and try something else; there’s no penalty (which honestly had never occurred to me until someone asked during the below-mentioned game; I replied politely that that’s done in the Draconian Rules version).

Then there are various potential rule negotiations that vary, some established at the start of play, but mostly decided whenever things come up. A not-quite exhaustive list of past negotiations:

- Do place names that no longer exist count? (Yugoslavia, Soviet Union)

- What if they’re archeological sites? (Xanadu)

- Do mythological places count? (Atlantis)

- Do other fictional places count? (Narnia)

- Can you leave earth? (Mars, Sea of Tranquility, Crab Nebula)

- When a place name starts with “The,” do we leave it off? (Netherlands)

- For places in non-English-speaking countries, do we use the English or local spelling? (Rome vs. Roma). What if you’re in that country at the time?

- Is “America” a place? (I say no, and I hold the line pretty hard.) *

- For rivers and mountains, do “river” and “mountain” count as part of the name? (Note: this query doesn’t seem to apply to “ocean,” which is generally included by default.)

- Do street names count? Do street names count if you’re desperate?

- If a place has changed its name, can you use the older name? (Leningrad vs. St. Petersburg). Can both be used in the same game?

One important discovery one makes while playing this game is that humans love the letter A.** There is often a point where we have what I call the “A cascade,” in which all the place names begin and end with A, for an impressively long time.***

Conversely, there are other letters that are very promising but rarely appear at the ends of names. A few years ago, I started compiling a list of places that end with uncommon letters. Naypyidaw, Edgecomb, Alcatraz, Czech Republic, Appomattax, and so on…

There is no winning. Play ends when players run out of options (though it’s fine to offer help), or enough people are done, or we arrive at a rest stop or destination. Occasionally we’ll try to pick up again afterward, but it’s tricky to keep the momentum going: in general we’ll either start over or move on to something else.

As you might imagine, playing two games of Geography in close succession can be tricky, since it becomes difficult to remember in which round a name was used. So we have alternate themes. As a kid, I often played a “first names” version, for which I was very pleased to know people named Yolanda (friend of my parents) and Yetta (my great-grandmother) and then extra pleased as a preteen to read an article about conjoined twins named Yvonne and Yvette. More recently, with my own kid and other family or friends, we’ve done it with plants (Negotiations: Use Latin names or only common? Does using both in the same game count as a repeat?) and animals (What about categories? If someone says sparrow, can you also say song sparrow?).

I recently returned from a chorus trip to Rome and Florence (or Roma e Firenze, but we decided on English spellings), and in one of the coach rides, there was a rousing game of Geography, with six people playing, plus a few others who offered suggestions or critiques. During play, the question of whether to allow fictional places came up, and my wife said firmly, “It would have to be only fictional places.” And while I started to talk through it out loud, one of the other players said, “But you could just make stuff up,” because anything you make up would be automatically fictional.

So I thought on it for a few days, and I now propose Geography, Fictional Places Edition:

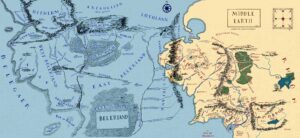

An overlay map in which the 1st Age map of Middle Earth from J.R.R.Tolkien’s Silmarillion is combined with the 3rd Age map from The Lord of the Rings. Image from The One Ring.

Player one names a fictional place. If everyone knows it, then you go on. If not everyone knows it, then you introduce it: “Alola is an island region from the Pokémon TV series; the main character travels there and makes new friends, and they go adventuring, making many discoveries,” or “Nangiyala is the afterlife in The Brothers Lionheart, which I read in an abbreviated form in Cricket magazine and still haven’t read as a full book.” If giving details about the place would provide plot spoilers, you can say so: give the citation but explain that saying more about the place itself would give too much away.

Authoring codicil: If everyone agrees, then yes, you can include places you’ve made up yourself, even on the spot, as long as you provide a good story to go along with it. And certainly if you’ve established them in prior writing.

Our first experiment, at home, has led to the recognition that I don’t keep a coherent list of fictional places in my head. On only the second turn, the kid said something that ended with D, and abruptly every place I had ever read about fell out of my head – musings throughout the trip notwithstanding. “Dreamland” sounded like something, but I wasn’t sure where to place it.**** Then I had to remind myself that Denmark wasn’t fictional. And then we had the first new question: about whether structures are places. “I want to say Dawn Treader,” I mused. Kid was skeptical when I reminded him it’s a boat. “But it’s the setting for most of the book!” I settled instead on Durmstrang, which while also a structure, at least was a stationary structure.***** And there was no objection, except now the kid was stuck on G.

We’ll see how it goes. (-:

With thanks to Jennifer Woodfin, Dan Rosen, and M. Sheffield for contributions and commentary, and Stephen Mayhew for an NER refresher.

———-

* While I do casually use “America” to mean the United States and “American” to refer to its residents, I have several reasons I don’t find it appropriate in a geographical naming setting.

The first is accuracy: the US of A implies that the US is a subpart of the lands of America. But the land mass is divided, and in English we don’t talk about “America” as the entire land mass. We have North America, South America, Central America, possibly the Americas (though then we have “the”). So if we do mean the US, then it’s an alternate name for the same country. If we don’t, then we have a name that’s not actually used that way.

Which brings us to the political argument: While I understand that “America” is short for “the United States of America,” it has bugged me that “America” refers specifically to the US since the time, many years ago in summer camp, when I wished a friend a happy 4th of July, and she said, “I’m not American,” reminding me that she was from Mexico. Holidays aside, it seemed profoundly unjust to me that someone from a country in North America couldn’t say they were American.******

** Well, sounds that are written in English as the letter A.

*** It’s great fun, but it’s also important to be able to end the cascade; I try to keep in mind a set of A names that end with something else: Arctic Circle, Arctic Ocean, Ambler…

**** Hm. With more time for reflection: Dreamland is both a place people go when they sleep and a favorite bedtime CD by Putamayo. I guess the former would work, then. Collective fiction!

***** But I kind of want the boat to count, too.

In the field of Natural Language Processing, there is a machine learning task called Named Entity Recognition. In NER, a computer model is trained to find proper names and categorize them, according to certain categories. In the project I helped on, there were four categories: Person, Organization, Location, and Geopolitical Entity. The distinction between GPE and LOC (which are both geographical) went as follows:

“GPE has a border, a government, and a population. LOC is a geographical region that doesn’t meet these criteria. So, the European Union has all 3 so it is a GPE. The Sahara desert may have a population and possibly a border, but no government, so it is LOC.”

Significantly, “Airports and other structures are LOC.”

But I don’t know about structures that actually change their location.

****** Speaking of the naming of the Americas: when we were in Florence last month, in the Accademia Gallery to see Michelangelo’s David, our local tour guide spoke to us about the Vespucci family. She first confirmed that we knew of the explorer Amerigo Vespucci, for whom the Americas were named.******* (She was not as surprised that we knew this as an earlier guide had been that we knew the name of Alessandro Botticelli – which for me would have been hard to avoid once my hair was long enough.) Then she explained that the Vespuccis were a well-known family in Florence, and that Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci, who had married into the family, became the subject of many of Botticelli’s paintings. (I was surprisingly gratified to learn that one of my artistic hair twins was based on a known person!) And it transpired that Botticelli specifically requested that he be buried near her, and so all three of them are buried with others of the family in a church in Florence. And then it turned out that the church in question, the Chiesa di Ognissanti, was the church in which we would be singing that evening!

******* And, wow, was I wrong about why the land was named for him.

The story I learned was that Amerigo Vespucci made a map of the lands he’d surveyed, and he wrote his name across it as a signature, but people thought it was meant to be the new name of the continent.

As it turns out, this part of the world was named for Amerigo Vespucci by other European mapmakers specifically to honor him, as the first European to recognize that they had not come around to the other side of Asia but instead had found an entire separate land in between.

https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2016/07/how-did-america-get-its-name/

(See also the comment therein about using America as a name)

Today (in the northern hemisphere) we welcome the Vernal Equinox — a time of balance — along with the full moon that heralds the arrival of Purim.*

Today (in the northern hemisphere) we welcome the Vernal Equinox — a time of balance — along with the full moon that heralds the arrival of Purim.*